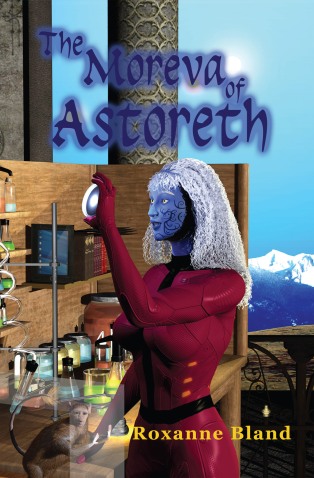

In the world-building tradition of Andre Norton, Anne McCaffrey and Ursula K. LeGuin, The Moreva of Astoreth is a blend of science fiction, romance, and adventure in a unique, richly imagined imperialistic society in which gods and science are indelibly intertwined. It is the story of the priestess, scientist, and healer Moreva Tehi, the spoiled, headstrong granddaughter of a powerful deity who is banished for a year to a volatile far corner of the planet for neglecting to perform her sacred duty, only to venture into dangerous realms of banned experimentation, spiritual rebirth, and fervent, forbidden love.

Chapter One

“I could have you executed for this, Moreva Tehi,” Astoreth said. My Devi grandmother, the Goddess of Love, scowled at me from Her golden throne in the massive Great Hall of Her equally massive Temple.

Sitting on my heels, I bowed my head and stared at the black and gold polished floor, trying to ignore the trickle of sweat snaking its way down my spine. “Yes, Most Holy One.”

“You blaspheme by not celebrating Ohra, My holiest of rites. And this one was important—the worthiest of the hakoi, handpicked by Me, celebrated with us. ”

“I can only offer my most abject apologies, Most Holy One.”

“Your apologies are not accepted.”

“Yes, Most Holy One.”

“Where were you?”

“I was in the laboratory, working on a cure for red fever. Many hakoi died last winter—”

“I know that,” my grandmother snapped. “But why did you miss Ohra? Did you not hear the bells?”

“Yes, Most Holy One. I heard them. I was about to lay aside my work when I noticed an anomaly in one of my pareon solutions. It was odd, so I decided to investigate. What I found…I just lost track of time.”

“You lost track of time?” Astoreth repeated, sounding incredulous. “Do you expect Me to believe that?”

“Yes, Most Holy One. It is the truth.”

A moment later, my head and hearts started to throb. I knew why. My grandmother was probing me for signs I had lied. But She wouldn’t find any. There was no point in lying to Astoreth, and it was dangerous, too. Swaying under the onslaught from Her power, I endured the pain without making a sound. After what seemed like forever the throbbing subsided, leaving me feeling sick and dizzy.

“Very well,” She said. “I accept what you say is true, but I still do not accept your apology.”

“Yes, Most Holy One.” I tried not to pant.

A minute passed in uncomfortable silence. Uncomfortable for me, anyway. Another minute passed. And another. Just when I thought maybe She was finished with me, Astoreth spoke. “What do you have against the hakoi, Moreva?”

The change of subject confused me. “What do you mean, Most Holy One?”

“I’ve watched you, Moreva. You give them no respect. You heal them because you must, but you treat them little better than animals. Why is that?”

The trickle of sweat reached the small of my back and pooled there. “But my work—”

“Your work is a game between you and the red fever. It has nothing to do with My hakoi.”

I didn’t answer right away. In truth, I despised Her hakoi. They were docile enough—the Devi’s breeding program saw to that—but most were slow-witted, not unlike the pirsu the Temple raised for meat and hide. They stank of makira, the pungent cabbage that was their dietary staple. From what I’d seen traveling through Kherah to Astoreth’s and other Gods’ Temples, all the hakoi were stupid and smelly, and I wanted nothing to do with them.

I did not want my grandmother to know what was in my hearts, so I chose my words carefully. “Most Holy One, I treat Your hakoi the way I do because it is the hierarchy of life as the Devi created it. You taught us the Great Pantheon of twelve Devi is Supreme. The lesser Devi are beneath You, the morevs are beneath the lesser gods, and Your hakoi are beneath the morevs. Beneath the hakoi are the plants and animals of Peris. But sometimes Your hakoi forget their place and must be reminded.” I held my breath, praying she wouldn’t probe me again.

Astoreth didn’t answer at first. “A pretty explanation, Moreva. But My hakoi know their place. It is you who do not know yours. You may be more Devi than morev but you are still morev, born of hakoi blood. You are not too good to minister to the hakoi’s needs, and you are certainly not too good to celebrate Ohra with them.”

I swallowed. “Yes, Most Holy One.”

“Look at me, Moreva.”

I raised my head. My grandmother’s expression was fierce.

“And that is why you let the time get away from you, as you say. You, Moreva Tehi, an acolyte of Love, are a bigot. That is why you did not want to share your body with My hakoi.” She leaned forward. “I have overlooked many of your transgressions while in My service, but I cannot overlook your bigotry or your missing Ohra. I will not execute you because you are too dear to My heart. The stewardship for Astoreth-

69 in the Syren Perritory ends this marun on eighth day. You will take the next rotation.”

My hearts froze. This was my punishment? Getting exiled to Syren? From what I’d heard from morevs serving in Astoreth’s other Temples, the Syren Perritory in Peris’s far northern hemisphere was the worst place in the world to steward a landing beacon. Cold and dark, with dense woods full of wild animals, the Syren was no place for me. My place was Kherah, a sunny desert south of the planet’s equator, where the fauna were kept in special habitats for learning and entertainment. As for the Syrenese, they were the product of one of the Devi’s earliest and failed experimental breeding programs, and were as untamed as the perritory in which they lived.

But I knew better than to protest. Astoreth’s word was law, and it had just come down on my head. “Yes, Most Holy One,” I said, my voice meek.

“Mehmed will come to your rooms after lunch tomorrow so you can be fitted for your uniform.”

“My uniform, Most Holy One? I will not be taking my clothes?”

“No. As overseer of the landing beacon, you are the liaison between the Mjor village as well as the commander of the garrison. Your subordinate, Kepten Yose, will report to you once a marun, and you are to relay the garrison’s needs to Laerd Teger, the Mjoran village chief.”

“Yes, Most Holy One.”

“I will make allowance for your healer’s kit and a portable laboratory, but you are not to take your work on red fever. I am sure you have other projects you can work on while you are there.”

“But—”

“No, Moreva. It is too dangerous.”

“I can take precautions—”

“No. That is My final word.” Astoreth leaned back in Her chair. Her eyes narrowed. “One more thing. You will be the only morev in Mjor, but that will not prevent you from observing Ohra. And you will do so with the garrison stationed there. Go now.”

I stood on shaky legs, bowed, and backed out of the Great Hall. Once in the corridor, I turned and fled to my quarters. I threw myself on the bed and sobbed. It was bad enough to be exiled to the Syren Perritory, but Ohra with the garrison? Only the hakoi served in Astoreth’s military. I felt dirty already. And not allowing me to work on my red fever project was punishment in itself.

A few minutes later I felt a hand on my shoulder. “Tehi, what’s wrong?” a worried voice said. It was Moreva Jaleta, one of my friendlier morev sisters.

“I-I’m being sent to the Syren Perritory to steward Astoreth-69,” I wailed.

Jaleta sat on the bed. “But why?”

I sat up. “I missed the last Ohra and n-now Astoreth is punishing me.”

Jaleta gave me an unsympathetic look. “You’re lucky she didn’t have your head. Be thankful you’re Her favorite.”

I sniffed but said nothing.

Jaleta patted me on the shoulder. “It won’t be so bad, Tehi. The year will be over before you know it. Come on, it’s time to eat.”

No comments:

Post a Comment